Ballast Water Systems: Essential Knowledge for Modern Ship Operations

A Naval Architect’s Guide to Understanding Ballast Water Management, Treatment Technologies, and Regulatory Compliance

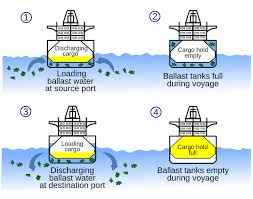

Ballast water systems remain one of the most critical yet often underappreciated aspects of ship design and operation. As naval architects and marine engineers, we must ensure these systems are properly designed, installed, and operated to maintain vessel stability, structural integrity, and environmental compliance.

The Fundamental Role of Ballast Water

Ballast water serves multiple essential functions in vessel operation. Ships carry ballast in fore and aft peaks, double bottom tanks, deep tanks, and side tanks depending on operational requirements. Ballast taken into the forward and aft ends adjusts the trim of the vessel, while double bottom and deep tanks are pumped to achieve proper draught and eliminate list. By weight, ballast water typically ranges from 10 to 17 percent of ship displacement—a substantial proportion that directly affects vessel performance and seakeeping characteristics.

The system operates on a centralised design principle where ballast tanks are filled and emptied through the same pipeline, necessitating careful valve arrangements. Classification societies and shipping registers stipulate the installation of stop and screw-down non-return valves to prevent seawater or ballast water from entering cargo holds, engine rooms, and boiler rooms. This redundancy is essential for maintaining watertight integrity throughout the vessel.

Design Considerations and Pipeline Arrangements

Several critical design requirements govern ballast system installation. Ballast pipelines must not pass through oil tanks located in double bottom spaces unless specific conditions are met: the tanks must have heating facilities, oil-resistant gaskets must be installed between flanges, and the pipeline must be hydraulically tested to 4 kg/cm². The sizing of inlet piping should correspond to the tank of maximum capacity to ensure adequate flow rates.

Ballast pumps, typically electric-motor-driven centrifugal units, must have sufficient capacity to empty tanks within 4 to 10 hours. The required pump capacity can be determined using the formula QB = 0.2825 × Db² × Vb², where Db represents the diameter of the inlet pipe of the largest ballast tank and Vb is the water flow velocity in the pump inlet line, typically 2 to 2.5 m/s.

Sea water enters the ballast system through a Kingston valve installed in the hull bottom or above the breast near the engine room. Tanks fitted below the waterline may be filled either by pump or by gravity. Vent pipes are essential to prevent air pockets during filling and vacuum conditions during pumping out, with their number and arrangement depending on compartment geometry.

Types of Ballast Tanks and Operational Flexibility

Modern vessels employ various ballast tank configurations to meet operational demands. Fuel ballast tanks can be rigged as either normal fuel oil tanks or main ballast tanks, providing operational flexibility. Variable water ballast is carried in forward and after trim tanks, as well as midship auxiliary tanks, permitting adjustment of both longitudinal moment and overall weight.

Permanent ballast, often using dense materials such as lead, iron, or concrete with dense aggregate, improves stability or removes list. For vessels found to be excessively stiff, permanent topside or tween deck ballast may be installed to reduce metacentric height. Liquid permanent ballast using fresh water with rust inhibitors offers lower material cost and easier removal compared to solid alternatives.

Challenges in Ballast Operations

Ballast exchange presents several operational challenges that masters and officers must navigate carefully. The introduction of salt water to recently emptied cargo tanks drives vapour into the atmosphere, with some ports restricting this practice due to air quality concerns. When cargo previously carried may have contained toxic substances, dirty ballast cannot be discharged at all, requiring careful planning of ballast operations.

Exchanging ballast while underway presents inherent dangers, particularly in heavy weather, as it can compromise vessel structural integrity. The process increases wear on ballast pumps, valves, and associated equipment while adding man-hours for monitoring and operation. These factors can potentially delay vessel schedules and impact commercial operations.

Treatment Technologies for Environmental Compliance

The IMO Ballast Water Management Convention has driven significant development in treatment technologies. Current approaches fall into three main categories: chemical biocides including ozone, chlorine, chlorine dioxide, and other biocidal agents; physical separation methods such as filtration and hydrocyclonic separation; and physical treatment methods including electrolytic treatment, ultraviolet light irradiation, deoxygenation, heat treatment, and electrical current application.

Many systems now combine multiple technologies, with typical installations featuring cyclone separators for initial removal of larger organisms and sediment, followed by UV treatment or chemical dosing for final disinfection. The selection of appropriate technology depends on vessel type, trading patterns, and operational requirements.

Operational Protocols and Safety Requirements

Each ballast pump typically features motor-operated suction and discharge valves with three operational modes: manual operation with the motor disengaged, electrical operation from the local controller, and remote operation. Stop-check valves or combined stop and check valve arrangements are required in each branch line, located inboard at least one-fifth of the vessel’s beam.

For vessels designed to carry combinations of liquid and dry bulk cargoes, ballast pumps and piping must not be located in machinery spaces other than cargo pump rooms, and simultaneous carriage of liquid and other cargoes is prohibited. These restrictions protect against cargo contamination and maintain operational safety standards.

Conclusion

Effective ballast water system design and operation requires careful integration of stability requirements, structural considerations, and environmental compliance. As treatment technology continues to evolve and regulations become more stringent, naval architects and marine engineers must stay current with best practices to deliver vessels that meet both operational demands and environmental responsibilities.

This article reflects the technical knowledge expected of marine professionals involved in vessel design, construction, and operation. For specific regulatory requirements, always consult the latest IMO conventions and flag state regulations.