Understanding Metacentric Height (GM) and Righting Lever (GZ): The Twin Pillars of Ship Stability

Every day, massive ships carrying thousands of containers cross rough oceans without capsizing. Small fishing boats return safely despite heavy catches and choppy waters. What keeps these vessels upright? The answer lies in two fundamental stability parameters: Metacentric Height (GM) and Righting Lever (GZ). These twin pillars of ship stability work together to ensure vessels can resist the tilting forces of waves, wind, and shifting cargo.

Understanding GM and GZ is essential for anyone involved in maritime operations, from ship designers to deck officers. While GM tells us about initial stability at small angles, GZ reveals how a ship behaves when tilted to larger angles. Together, they provide a complete picture of a vessel’s ability to stay upright and return to its normal position after being disturbed.

Let’s explore these critical concepts in simple terms that anyone can understand.

What is Metacentric Height (GM)?

Definition and Basic Concept

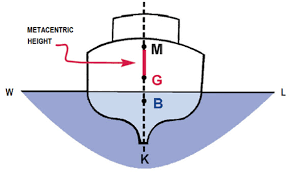

Metacentric Height (GM) is the vertical distance between two important points on a ship:

- G = Center of Gravity (the point where all the ship’s weight appears to act)

- M = Metacentre (the theoretical point explained in our article)

Think of GM as a measuring stick that tells you how “stiff” or stable a ship is when tilted at small angles (typically less than 10-15 degrees). The larger the GM, the stronger the ship’s tendency to return upright.

The Three Stability States

According to Ship Stability for Masters and Mates by Barrass and Derrett, a ship can exist in three stability states based on GM:

1. Positive GM (Stable Equilibrium)

When the metacentre (M) is above the center of gravity (G), GM is positive. The ship is stable and will return to upright position after tilting. Most commercial vessels operate with positive GM ranging from 0.5 to 3.0 meters, depending on vessel type.

2. Negative GM (Unstable Equilibrium)

When the metacentre (M) is below the center of gravity (G), GM is negative. This dangerous condition means the ship will continue rolling over if tilted. Negative GM must be avoided at all costs—it’s the primary cause of capsizing accidents.

3. Neutral Equilibrium (Zero GM)

When the metacentre and center of gravity coincide (M = G), GM equals zero. The ship will stay in whatever tilted position it’s placed, neither returning upright nor capsizing further. This unstable condition is also dangerous in real sea conditions.

How to Calculate GM

The basic formula for metacentric height is:

GM = KM – KG

Where:

- KM = Height of metacentre above the keel (baseline)

- KG = Height of center of gravity above the keel

Naval architects calculate these values using the ship’s geometry, weight distribution, and loading condition. The Principles of Naval Architecture series provides detailed calculation methods.

Typical GM Values for Different Vessels

Different ship types require different GM values:

- Container Ships: 1.0 – 2.5 meters

- Bulk Carriers: 0.8 – 2.0 meters

- Tankers: 0.5 – 1.5 meters

- Passenger Ships: 1.5 – 3.0 meters (higher for passenger comfort and safety)

- Fishing Vessels: 0.6 – 1.5 meters

- Naval Vessels: 1.0 – 2.0 meters

The International Maritime Organization sets minimum GM requirements through the International Code on Intact Stability.

The GM Paradox: Too Much is Bad Too

While positive GM is essential, excessively large GM creates problems:

Advantages of Large GM:

- Strong righting ability

- Quick recovery from tilting

- Greater safety margin against capsizing

Disadvantages of Large GM:

- Rapid, jerky rolling motion

- Passenger discomfort and seasickness

- Increased structural stress

- Cargo shifting risk

- Equipment damage

Naval architects must find the optimal GM—large enough for safety but small enough for comfortable motion. This balance varies with vessel purpose and operating environment.

What is Righting Lever (GZ)?

Definition and Physical Meaning

The Righting Lever (GZ) is the horizontal distance between two vertical lines:

- A vertical line through the center of gravity (G)

- A vertical line through the center of buoyancy (B)

When a ship tilts to an angle θ (theta), the underwater shape changes, causing the center of buoyancy to shift sideways. The horizontal separation between G and B creates the righting lever, measured in meters.

Unlike GM which applies only at small angles, GZ describes stability at any angle of heel, from 0 degrees to 90 degrees or beyond.

Understanding Righting Moment

The righting lever GZ is used to calculate the righting moment—the actual force trying to bring the ship upright:

Righting Moment = Displacement × GZ

Or more commonly:

Righting Moment = W × GZ

Where:

- W = Ship’s displacement (weight) in tonnes

- GZ = Righting lever in meters

- Righting Moment = Force in tonne-meters

This righting moment must overcome the heeling moment caused by wind, waves, or cargo shifts to keep the ship upright.

The GZ Curve (Curve of Statical Stability)

Naval architects plot GZ values against heel angles to create the GZ curve or curve of statical stability. This graph reveals everything about a ship’s stability characteristics.

Key Features of a GZ Curve

According to Basic Ship Theory by Rawson and Tupper, a healthy GZ curve should have:

1. Maximum GZ (GZ_max) The highest point on the curve, typically occurring between 30-40 degrees of heel. Larger maximum GZ means stronger righting ability.

2. Range of Stability The heel angle range where GZ remains positive (ship has righting moment). A good range extends from 0 degrees to 60-80 degrees or more.

3. Angle of Vanishing Stability The angle where GZ becomes zero and the curve crosses the horizontal axis. Beyond this angle, the ship will capsize.

4. Area Under the Curve Represents the energy required to capsize the ship. Larger area means greater dynamic stability—the ability to absorb wave impacts.

5. Initial Slope The steepness of the curve at zero degrees relates directly to GM. Steeper initial slope indicates larger metacentric height.

Relationship Between GM and GZ

For small angles (typically under 10-15 degrees), there’s a mathematical relationship:

GZ ≈ GM × sin(θ)

Where θ is the heel angle in degrees.

This approximation shows that GM determines the initial portion of the GZ curve. However, at larger angles, the ship’s actual geometry dominates, and this simple formula no longer applies. Research published in the Journal of Ship Research demonstrates the importance of understanding both small-angle (GM) and large-angle (GZ curve) stability.

Practical Applications in Ship Operations

During Cargo Loading

Before loading cargo, ship officers must verify:

- GM Requirements: Ensuring metacentric height stays above minimum values specified in the stability booklet

- GZ Curve Compliance: Checking that the loading condition produces an acceptable GZ curve meeting regulatory requirements

The American Bureau of Shipping provides detailed guidance on stability calculations during loading operations.

In Heavy Weather

When sailing through storms, both GM and GZ become critical:

- GM determines how quickly the ship rolls in waves

- GZ curve area determines whether the ship can survive large wave impacts without capsizing

Captains may alter course or speed based on stability characteristics to ensure safe passage.

For Damage Stability

If a ship is damaged and flooded, both GM and GZ change dramatically:

- Flooding increases KG (raises center of gravity)

- Water ingress changes the underwater shape

- Both effects reduce GM and alter the GZ curve

- Naval architects analyze damage scenarios to ensure ships can survive with certain compartments flooded

The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) requires passenger ships to maintain positive stability even with specific compartments flooded.

Real-World Case Studies

The Herald of Free Enterprise Disaster (1987)

This ro-ro ferry capsized in 1987, killing 193 people. Investigation revealed inadequate GM due to:

- Bow doors left open, allowing water on vehicle deck

- Free surface effect of water reducing GM

- Ship capsizing in less than 90 seconds

This tragedy led to major improvements in ro-ro ferry stability regulations and GM requirements.

Modern Container Ship Stability

Modern ultra-large container ships stack containers 20+ layers high. This raises the center of gravity significantly, reducing GM. Naval architects must:

- Carefully plan container distribution

- Use ballast water to lower KG

- Monitor GM continuously during loading

- Ensure GZ curve meets International Maritime Organization criteria

Fishing Vessel Operations

Small fishing vessels face unique challenges:

- Variable loading when nets are filled

- Top-heavy gear (masts, winches)

- Free surface effect from water and fuel tanks

Many fishing vessel casualties result from insufficient attention to GM during catch operations. Studies show proper understanding of GM and GZ could prevent numerous accidents.

Regulatory Requirements

IMO Intact Stability Code

The International Code on Intact Stability requires:

For GM:

- Minimum GM values based on vessel type

- Typically 0.15m minimum for small vessels

- Larger values for passenger ships and certain cargo vessels

For GZ Curve:

- Area under GZ curve ≥ 0.055 meter-radians up to 30° heel

- Area under GZ curve ≥ 0.09 meter-radians up to 40° heel

- Area between 30° and 40° ≥ 0.03 meter-radians

- GZ_max ≥ 0.20 meters at angles ≥ 30°

- Maximum GZ occurs at angles > 30° (preferably approaching 40°)

- Range of positive GZ extends to at least 60°

Class Society Requirements

Classification societies like Lloyd’s Register, DNV, and ABS impose additional requirements based on vessel type and trading area.

Monitoring and Measurement

Inclining Experiment

New ships undergo an inclining experiment to determine actual KG and verify GM. This test involves:

- Moving known weights across the deck

- Measuring the resulting heel angle

- Calculating GM from the relationship between weight movement and heel

- Determining actual KG and comparing with design values

The Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers publishes detailed procedures in the Principles of Naval Architecture series.

Onboard Stability Computers

Modern vessels carry loading computers that:

- Calculate GM and plot GZ curves in real-time

- Account for cargo, fuel, ballast, and consumables

- Warn officers when stability becomes marginal

- Store approved loading conditions from the stability booklet

Stability Booklets

Every commercial vessel carries an approved stability booklet containing:

- GZ curves for various loading conditions

- Maximum allowable KG values

- Minimum GM requirements

- Loading instructions and limitations

- Guidance for different operational scenarios

Conclusion

Metacentric Height (GM) and Righting Lever (GZ) form the foundation of ship stability analysis. While GM provides a quick measure of initial stability and determines how “stiff” a ship feels in small waves, the GZ curve reveals the complete stability picture across all angles of heel.

Together, these parameters ensure that:

- Ships can safely carry cargo without capsizing

- Vessels survive heavy weather and damage scenarios

- Passengers and crew remain safe during all operations

- Regulatory requirements are met

For maritime professionals, understanding both GM and GZ is not merely academic—it’s essential for safe ship operation. From the design office to the loading dock, from calm harbors to stormy seas, these stability parameters guide every decision affecting vessel safety.

Modern naval architecture combines traditional stability principles with advanced computer simulation, but the fundamental concepts of GM and GZ remain unchanged. Visit Nautical Voice for more in-depth articles on maritime engineering and ship stability.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What’s the difference between GM and GZ?

GM (metacentric height) measures initial stability at small heel angles (0-10 degrees) and tells you how quickly a ship returns upright from small disturbances. GZ (righting lever) measures stability at any heel angle and tells you the actual righting force available. GM is a single number in meters, while GZ varies with heel angle and is plotted as a curve. Think of GM as a quick stability check, while GZ provides the complete stability story.

2. Can a ship with good GM still capsize?

Yes, absolutely. While positive GM ensures initial stability, a ship can still capsize if the GZ curve is poor at larger angles. For example, a ship might have adequate GM but a small range of stability (GZ becomes negative at low angles like 40 degrees). In severe weather or damage scenarios, the ship could heel beyond its range of positive stability and capsize despite having acceptable GM initially.

3. How do free surface effects impact GM and GZ?

Free surface effect occurs when liquids (fuel, ballast, cargo) can slosh in partially filled tanks. This effectively raises the center of gravity and reduces GM, sometimes dramatically. The larger the tank and the wider it is, the greater the effect. Free surface also negatively impacts the GZ curve, reducing maximum GZ and the range of stability. This is why ships should sail with tanks either full or empty when possible, and why tanks have subdivision to limit free surface.

4. Why do passenger ships need higher GM than cargo ships?

Passenger ships require higher GM for two main reasons: safety and comfort. Higher GM provides greater safety margins against capsizing, critical when carrying hundreds or thousands of passengers. However, there’s a balance—too much GM causes rapid, jerky rolling that makes passengers seasick and uncomfortable. Passenger ships typically aim for GM values of 1.5-3.0 meters, higher than most cargo vessels but not so high as to create harsh motion characteristics.

5. How often should GM and GZ be calculated during a voyage?

GM and GZ should be calculated whenever the loading condition changes significantly. This includes: before departure (after loading), when consuming significant amounts of fuel (typically daily on long voyages), when transferring ballast, when loading or discharging cargo at ports, and before entering heavy weather. Modern stability computers make these calculations quick and easy, allowing continuous monitoring. Some vessels are required to calculate stability before each voyage leg, while others must do so daily or when conditions change materially.

References and Further Reading

Standard Textbooks:

- Barrass, C.B., and Derrett, D.R. Ship Stability for Masters and Mates, 7th Edition, Butterworth-Heinemann – Publisher Link

- Rawson, K.J., and Tupper, E.C. Basic Ship Theory, Volume 1, 5th Edition, Butterworth-Heinemann – Publisher Link

- Principles of Naval Architecture Series, Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers (SNAME) – SNAME Publications

- Biran, A., and Pulido, R.L. Ship Hydrostatics and Stability, 2nd Edition, Butterworth-Heinemann

International Regulations and Standards:

- International Maritime Organization (IMO) – https://www.imo.org

- International Code on Intact Stability, 2008 (IS Code) – IMO Stability Code

- International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) – SOLAS Convention

Historical Case Studies:

- Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) Reports – https://www.gov.uk/maib-reports

- Transportation Safety Board of Canada Marine Reports

- National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) Marine Accident Reports