Archimedes’ Principle and Its Application to Ship Stability

Every naval architect begins their journey with one fundamental question: how does a 200,000-tonne steel vessel float while a small iron nail sinks? The answer lies in a discovery made over two thousand years ago by a Greek mathematician in his bathtub.

Understanding Archimedes’ Principle

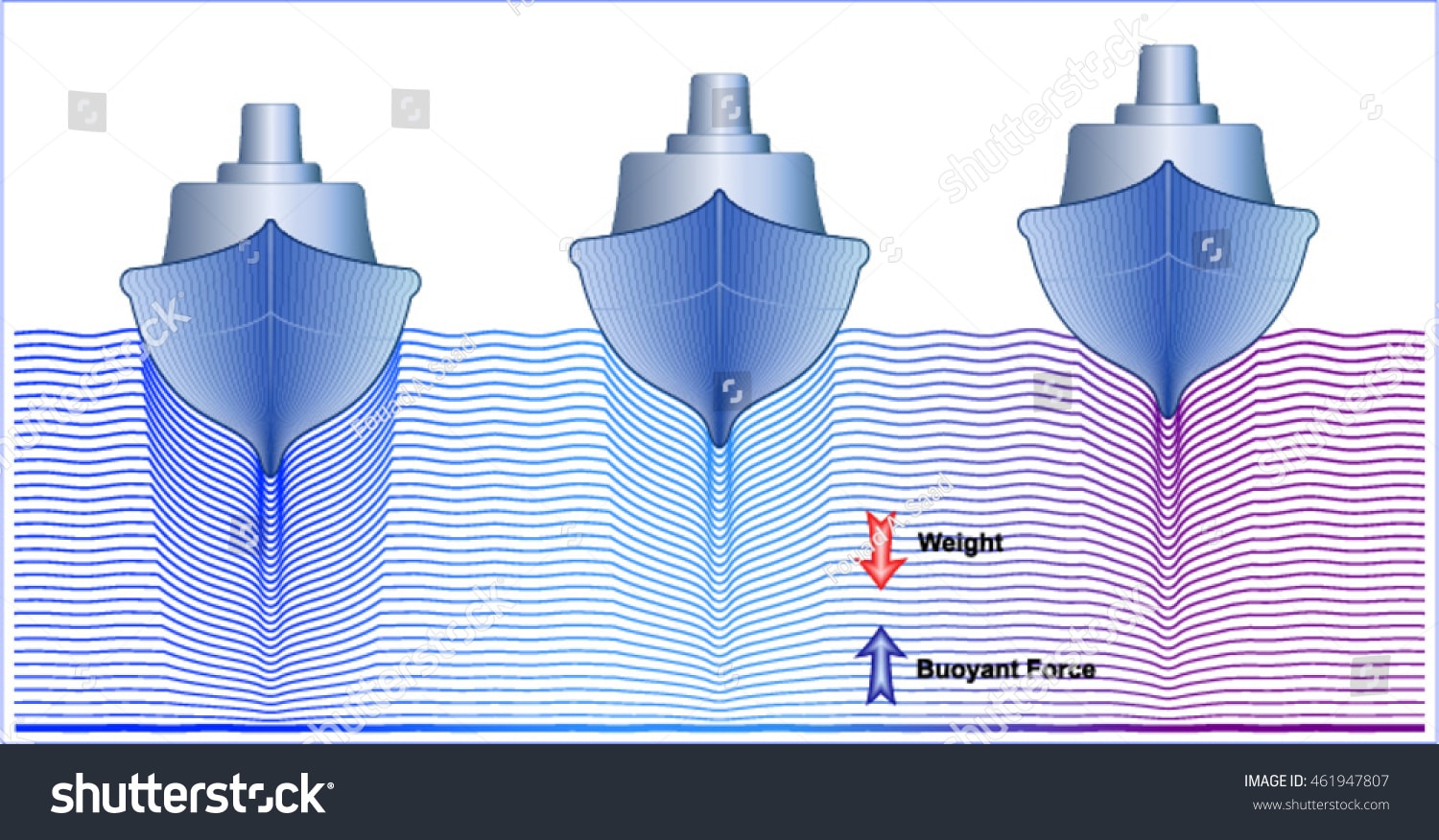

Archimedes’ Principle states that when a body is wholly or partially immersed in a fluid, it experiences an upward force equal to the weight of the fluid it displaces. This upward force is called buoyancy.

In simple terms, if you push a beach ball underwater, you feel the water pushing it back up. The harder you push it down (displacing more water), the stronger the upward push becomes. This is buoyancy in action.

The principle can be expressed as:

Buoyant Force = Weight of Displaced Fluid = ρ × g × V

Where ρ is the density of the fluid, g is gravitational acceleration, and V is the volume of fluid displaced.

For a body to float, the buoyant force must equal its weight. A ship floats because it displaces a volume of water whose weight equals the total weight of the ship.

Why Ships Float Despite Being Made of Steel

This is perhaps the most common question I encounter from young engineers. Steel has a density of approximately 7,850 kg/m³, nearly eight times that of seawater at 1,025 kg/m³. By all accounts, steel should sink.

The key lies in the ship’s shape. A solid block of steel will sink because it displaces very little water relative to its weight. However, when we form that same steel into a hollow hull, we create a large enclosed volume. The ship now displaces an enormous quantity of water while the actual steel weight remains the same.

Consider a simple example. A solid steel cube measuring 1 metre on each side weighs approximately 7,850 kg. It displaces only 1 cubic metre of seawater, providing a buoyant force of just 1,025 kg. The cube sinks because its weight far exceeds the buoyancy.

Now imagine reshaping that same steel into a hollow box measuring 3 metres long, 2 metres wide, and 1.5 metres deep, with thin walls. This box can displace up to 9 cubic metres of water, generating a maximum buoyant force of over 9,000 kg. The steel weight remains 7,850 kg, but now buoyancy can easily support it. The box floats with considerable reserve.

This is precisely how ships work. The hull encloses air, creating displacement volume far greater than what solid steel could achieve.

The Floating Equilibrium

For a vessel to float in equilibrium, two conditions must be satisfied. First, the weight of the vessel must equal the weight of water displaced. Second, the centre of gravity of the vessel and the centre of buoyancy must be vertically aligned.

The centre of buoyancy is the geometric centre of the underwater volume. It represents the point through which the buoyant force acts upward. The centre of gravity is the point through which the vessel’s weight acts downward.

When a ship is designed, naval architects carefully calculate both points. During loading operations, cargo placement directly affects the centre of gravity position, which in turn influences stability.

Application to Ship Stability

Stability refers to a vessel’s ability to return to its upright position after being disturbed by external forces such as waves, wind, or cargo shifting. Archimedes’ Principle forms the foundation of all stability calculations.

When a ship heels (tilts) to one side, the underwater shape changes. The centre of buoyancy shifts toward the lower side because more volume is now submerged there. This shift creates a righting moment that pushes the vessel back upright.

The metacentre is a critical concept derived from this behaviour. It is the point where the vertical line through the shifted centre of buoyancy intersects the vessel’s centreline. The distance between the centre of gravity and the metacentre, called the metacentric height (GM), determines initial stability.

A positive GM means the metacentre lies above the centre of gravity. When the ship heels, the buoyant force creates a righting moment that restores the vessel to upright. This is stable equilibrium.

A negative GM indicates the metacentre lies below the centre of gravity. Any heel angle causes a capsizing moment rather than a righting moment. The vessel will continue to heel until it capsizes or reaches a new equilibrium at a large angle. This condition is dangerous and must be avoided.

Practical Examples in Ship Operations

Consider a container vessel loading cargo at port. Heavy containers placed high on deck raise the centre of gravity. If raised excessively, GM becomes dangerously small or negative. The vessel loses stability and may capsize even in calm water. This is why cargo loading computers continuously monitor stability during operations.

Ballast water management provides another practical application. When a tanker discharges cargo, it loses weight from low in the hull. The centre of gravity rises relative to the keel. To maintain adequate stability, ballast water is pumped into double bottom tanks, adding weight low in the vessel and lowering the centre of gravity.

Free surface effect demonstrates Archimedes’ Principle in a different way. Partially filled tanks allow liquid to shift when the vessel heels. This movement effectively raises the centre of gravity, reducing GM. Naval architects account for this by designing tank arrangements that minimise free surface effects during typical loading conditions.

Conclusion

Archimedes’ Principle is not merely a theoretical concept from ancient Greece. It is the working foundation upon which every floating vessel operates. From the initial hull design to daily loading operations and emergency response, understanding how buoyancy interacts with weight distribution determines whether a ship sails safely or faces catastrophic failure. For naval architects and marine engineers, this principle remains as relevant today as it was when Archimedes first stepped into his bath.