Understanding the Difference Between Intact Stability and Damage Stability

Every ship operating at sea must demonstrate its ability to remain upright and recover from external disturbances. This ability is assessed under two fundamentally different conditions: when the hull is complete and watertight, and when the hull has been breached allowing water ingress. These two scenarios form the basis of intact stability and damage stability assessments, both essential for safe vessel operation.

What is Intact Stability?

Intact stability refers to a vessel’s ability to resist capsizing and return to its upright position when all watertight boundaries remain undamaged. The hull is complete, no flooding has occurred, and the ship operates under normal conditions.

When naval architects design a vessel, intact stability is the first stability condition they analyse. It considers the vessel’s response to external forces such as wind, waves, passenger movement, cargo shifting, and turning manoeuvres. The assessment assumes the hull integrity is perfect throughout the voyage.

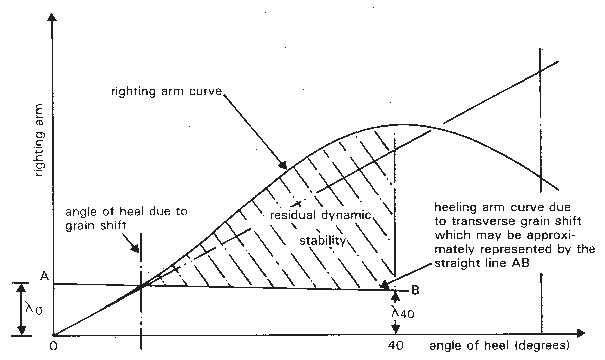

Intact stability criteria are defined by international regulations, primarily the International Maritime Organization’s Intact Stability Code (IS Code 2008). These criteria specify minimum requirements for righting lever curves, metacentric height, and dynamic stability under various loading conditions.

The key parameters evaluated in intact stability include initial metacentric height (GM), righting lever values (GZ) at specific heel angles, maximum righting lever angle, range of positive stability, and area under the GZ curve. Each parameter has prescribed minimum values that the vessel must satisfy across all anticipated loading conditions.

For example, a typical cargo vessel must maintain a minimum GM of 0.15 metres, a maximum GZ occurring at an angle not less than 25 degrees, and positive stability range extending to at least 60 degrees. These values ensure the vessel can withstand normal operational disturbances without capsizing.

What is Damage Stability?

Damage stability assesses a vessel’s ability to survive and remain afloat after the hull has been breached. Water enters the ship through the damage opening, flooding one or more compartments. The vessel must still possess sufficient residual stability to resist capsizing despite this flooding.

Damage stability analysis assumes the worst has already happened. A collision has punctured the side shell, a grounding has torn open the bottom plating, or structural failure has compromised watertight boundaries. The question becomes whether the vessel can survive long enough for passengers and crew to evacuate safely or for salvage operations to commence.

The flooding changes everything about the vessel’s stability characteristics. The centre of gravity shifts due to added water weight. The centre of buoyancy moves as the underwater hull form changes. Free surface effects from partially flooded compartments reduce effective GM. The vessel typically heels and trims to a new equilibrium position, often with significantly reduced freeboard.

International regulations governing damage stability are found in SOLAS (Safety of Life at Sea) for passenger ships and cargo vessels, MARPOL for tankers, and the International Code on Intact Stability for various vessel types. These regulations have become increasingly stringent following major maritime casualties.

Key Differences Between the Two Conditions

The fundamental difference lies in hull integrity. Intact stability assumes a perfect, undamaged hull where the designer controls all variables. Damage stability assumes the hull has failed, and the analysis determines survivability under adverse circumstances.

Loading conditions differ significantly between the two assessments. Intact stability evaluates normal operational loadings including departure, arrival, ballast, and intermediate conditions. Damage stability evaluates the same vessel after flooding, with additional water weight, changed trim, and altered freeboard.

The purpose of each assessment varies considerably. Intact stability ensures the vessel can operate safely during routine voyages. Damage stability ensures the vessel provides adequate time for evacuation and emergency response after an accident.

Regulatory requirements reflect these different purposes. Intact stability criteria focus on preventing capsizing during normal operations through adequate righting moment and range. Damage stability criteria focus on survival after flooding through residual stability, permeability calculations, and progressive flooding analysis.

The mathematical approach also differs. Intact stability uses straightforward hydrostatic calculations with fixed hull geometry. Damage stability requires complex flooding simulations considering permeability of spaces, cross-flooding arrangements, progressive flooding sequences, and time-dependent water ingress.

Practical Examples

Consider a passenger ferry operating coastal routes. For intact stability, the naval architect analyses the vessel with full passenger complement on the car deck, accounting for wind heeling, turning forces, and passenger crowding on one side. The vessel must maintain positive stability throughout these scenarios.

For damage stability, the same ferry is analysed assuming a collision has breached the side shell. Regulations typically require the vessel to survive flooding of any single compartment or group of adjacent compartments within specified damage extent. The ferry must remain afloat with sufficient residual stability for orderly passenger evacuation, typically with a final waterline below the margin line and positive residual GM.

A crude oil tanker provides another illustration. Intact stability analysis ensures the vessel remains stable during loading, voyage, and discharge operations, accounting for free surface effects in partially filled cargo tanks and ballast tanks.

Damage stability for the same tanker under MARPOL regulations requires survival after bottom or side damage. The damage extent is prescribed based on ship length and tank arrangement. The tanker must demonstrate that flooding of damaged tanks does not result in capsizing or excessive oil outflow. This requirement has driven the adoption of double hull construction in modern tankers.

Why Both Assessments Matter

A vessel satisfying intact stability requirements may fail damage stability criteria, and vice versa. A ship with excellent intact stability but poor subdivision will sink rapidly after damage. Conversely, a heavily subdivided vessel may survive damage but exhibit poor intact stability during normal operations.

The 1912 Titanic disaster demonstrated the consequences of inadequate damage stability despite acceptable intact stability. The vessel remained stable during normal operations but sank within hours after collision damage flooded multiple compartments beyond the design assumptions.

Modern regulations require both assessments because they address different failure modes. Intact stability prevents capsizing during routine operations. Damage stability ensures survivability after accidents. Together, they provide comprehensive protection for vessels, crew, passengers, and cargo across the full spectrum of operating conditions and potential casualties.

Understanding this distinction is essential for naval architects during design, for ship officers during loading operations, and for marine surveyors during statutory inspections. Both conditions must be satisfied for a vessel to be considered safe for its intended service.