What is the Metacentre in Ship Stability: Understanding This Theoretical Point

Imagine trying to balance a ruler on your finger. If you tilt it slightly, it either falls over or returns to its original position. Ships work on a similar principle, but instead of your finger, they rely on an invisible point called the metacentre. This theoretical point determines whether a ship will stay upright or capsize when waves tilt it sideways. Understanding the metacentre is essential for anyone working in maritime safety and ship design.

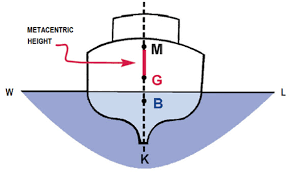

The metacentre, denoted by the letter M, is one of the most important concepts in naval architecture, yet it remains invisible and cannot be touched. Let’s explore what makes this point so crucial for keeping ships safe at sea.

What Exactly is the Metacentre?

The metacentre is a theoretical point located above a floating ship where imaginary vertical lines intersect. To understand this better, we need to know about another point called the center of buoyancy (B).

Understanding the Center of Buoyancy

When a ship floats in water, the water pushes upward with a force called buoyancy. This upward force acts through a single point called the center of buoyancy, which is simply the geometric center of the part of the ship that’s underwater. Think of it as the “balance point” of the submerged portion.

How the Metacentre Forms

When waves tilt a ship to one side, the underwater shape changes. More of one side goes underwater while the other side comes up. This causes the center of buoyancy to shift sideways. If you draw vertical lines through the center of buoyancy at different tilt angles, these lines meet at a single point called the metacentre.

According to the textbook Basic Ship Theory by Rawson and Tupper, the metacentre represents “a geometric construction that helps predict ship behavior during rolling motion.”

Why is the Metacentre Called “Theoretical”?

The term “theoretical” might sound confusing, but there are clear reasons why naval architects use this word:

1. You Cannot See or Touch It

Unlike physical parts of a ship like the anchor, propeller, or rudder, the metacentre doesn’t exist as a real object. You cannot walk to it, paint it, or point at it. It exists only in calculations, drawings, and computer simulations. Naval architects calculate its position using mathematical formulas based on the ship’s shape and how deep it sits in the water.

2. It Constantly Changes Position

The metacentre is not fixed in one place. Its position moves depending on:

- How much cargo is loaded: A fully loaded ship has a different metacentre position than an empty one

- Fuel consumption: As the ship uses fuel during a voyage, the metacentre shifts

- Ballast water adjustments: Adding or removing ballast water changes where the metacentre sits

- Ship’s draft: How deep the ship sits in water directly affects the metacentre location

Research published in the Journal of Ship Research shows that tracking these changes is critical for maintaining vessel safety throughout a voyage.

3. Valid Only for Small Tilting Angles

The metacentre concept works accurately only when a ship tilts at small angles, typically less than 10-15 degrees. Beyond this range, the mathematical relationship becomes unreliable, and naval architects must use more complex methods. This limitation makes it an approximation—a useful tool for specific conditions rather than an absolute physical reality.

The International Code on Intact Stability published by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) acknowledges these limitations while establishing safety standards.

The Critical Concept: Metacentric Height

What is Metacentric Height (GM)?

The vertical distance between the metacentre (M) and the ship’s center of gravity (G) is called the metacentric height, abbreviated as GM. This single measurement tells us everything about a ship’s stability:

- Positive GM (M is above G): The ship is stable and will return upright after tilting

- Negative GM (M is below G): The ship is unstable and will capsize

- Zero GM (M and G coincide): The ship stays tilted and won’t recover or capsize further

Why GM Matters More Than M Alone

While the metacentre’s position is important, what really matters for safety is the metacentric height. A ship needs sufficient GM to generate a righting moment—the force that brings it back upright after waves tilt it. Too little GM makes ships dangerously unstable, while too much causes uncomfortable rolling for passengers and crew.

According to Ship Stability for Masters and Mates by Barrass and Derrett, different types of vessels require different GM values. Passenger ships need higher GM for safety, while cargo ships can operate with moderate values.

How Naval Architects Use the Metacentre

During Ship Design

When designing a new vessel, naval architects calculate the metacentre position for every possible loading condition. They create detailed stability booklets that show how M and GM change with different:

- Cargo distributions

- Fuel levels

- Ballast configurations

- Water depths (draft)

Modern ship design relies heavily on computer software that simulates thousands of scenarios to ensure the metacentre remains in safe positions under all circumstances.

During Ship Operations

Ship officers use stability information daily when loading cargo. Before loading containers, bulk cargo, or liquids, they consult stability calculations to ensure the operation won’t reduce GM to dangerous levels. Modern vessels have stability computers that continuously monitor these values and alert crew if stability deteriorates.

The American Bureau of Shipping provides technical guidance on these calculations and requires ships to maintain minimum GM values based on vessel type and operating conditions.

In Stability Investigations

When maritime accidents occur, investigators examine whether stability principles were followed. The 2012 Costa Concordia disaster, where a cruise ship capsized off Italy, involved stability calculations. Flooding after the ship struck rocks caused the center of gravity to shift upward while the center of buoyancy moved, effectively reducing metacentric height until the vessel became unstable and capsized.

Real-World Examples

Container Ships

Large container ships stack containers many layers high. Each container added raises the ship’s center of gravity. Naval architects must ensure that even with maximum container stacking, the metacentre remains sufficiently above the center of gravity to maintain positive GM.

Fishing Vessels

Fishing boats face unique challenges. When they fill their nets with a large catch, the weight distribution changes dramatically. The metacentre position must account for these rapid changes to prevent capsizing—a significant cause of fishing vessel accidents worldwide.

Naval Vessels

Warships like destroyers and frigates must maintain stability even when carrying heavy weapons systems high on the superstructure. Defense engineers carefully calculate how these top-heavy loads affect the metacentre and overall stability.

Mathematical Foundation (Simplified)

Without getting too technical, the metacentre’s height above the keel (baseline of the ship) is calculated using:

KM = KB + BM

Where:

- KM = Height of metacentre above keel

- KB = Height of center of buoyancy above keel

- BM = Metacentric radius (calculated from ship’s waterplane shape)

The formula for BM is: BM = I / V

Where:

- I = Second moment of area of the waterplane (ship’s “footprint” on water)

- V = Volume of underwater portion

These calculations, detailed in the Principles of Naval Architecture series by the Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers, form the basis of all stability analysis.

Conclusion

The metacentre stands as one of naval architecture’s most important yet misunderstood concepts. Though theoretical, invisible, and constantly shifting, it provides the mathematical foundation that keeps ships upright in rough seas. Understanding why this point is theoretical—because it cannot be physically located, changes with loading conditions, and applies only to small angles—helps explain why ship stability requires constant attention from both designers and operators.

Modern maritime safety depends on respecting the principles governing the metacentre. From the design office to the loading dock, from calm harbors to stormy oceans, this theoretical point influences every decision affecting vessel stability.

For aspiring naval architects and maritime professionals, mastering the metacentre concept opens the door to understanding how physics and mathematics work together to keep massive steel structures safely afloat across the world’s oceans. Visit Nautical Voice for more maritime engineering insights.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Can the metacentre ever be below the center of gravity?

Yes, when the metacentre falls below the center of gravity (negative GM), the ship becomes unstable and will capsize if tilted. This dangerous condition must be avoided through proper loading, ballasting, and following the vessel’s stability booklet. Most maritime accidents involving capsizing result from negative or insufficient metacentric height.

2. How do ships with different shapes have different metacentres?

Ship shape dramatically affects the metacentre position. Wide, flat-bottomed ships (like barges) have metacentres located high above the center of gravity, making them very stable. Narrow, deep ships have lower metacentres and may be less stable but roll more gently. Naval architects choose shapes based on the vessel’s intended purpose—stability for cargo ships versus seakeeping for passenger vessels.

3. Does the metacentre apply to submarines?

Submarines use metacentre principles differently. When surfaced, submarines follow the same stability rules as surface ships. When submerged, they operate on different principles because the entire vessel is underwater. Submarines control their depth and stability by adjusting ballast tanks, effectively controlling where their center of gravity and center of buoyancy sit relative to each other.

4. Why don’t ships just make the metacentre as high as possible for maximum stability?

While a high metacentre creates greater stability, it also causes uncomfortable, rapid rolling motion. Passenger ships need balance—enough GM for safety but not so much that passengers get seasick from harsh, jerky movements. Cargo ships carrying liquids face different challenges, as excessive GM can cause dangerous sloshing. Naval architects optimize GM for each vessel’s specific operational requirements.

5. How has computer technology changed how we calculate the metacentre?

Modern naval architecture software can calculate the metacentre position in seconds for thousands of loading scenarios, something that would take weeks by hand. These programs create 3D models of ships and simulate how they behave in various sea conditions. However, the fundamental principles remain the same—computers simply make the calculations faster and more accurate. Ships now carry onboard stability computers that continuously monitor GM and alert officers to dangerous conditions.

References and Further Reading

Books and Educational Resources:

- Rawson, K.J., and Tupper, E.C. Basic Ship Theory, Volume 1, Butterworth-Heinemann – Publisher Link

- Barrass, C.B., and Derrett, D.R. Ship Stability for Masters and Mates, Butterworth-Heinemann – Publisher Link

- Principles of Naval Architecture Series, Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers (SNAME) – SNAME Publications

Maritime Organizations and Standards:

- International Maritime Organization (IMO) – https://www.imo.org

- International Code on Intact Stability, 2008 – IMO Stability Standards

- American Bureau of Shipping (ABS) – https://ww2.eagle.org

- Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers – https://www.sname.org

Academic Journals:

- Journal of Ship Research – SNAME Journal

- Ocean Engineering Journal – Research on ship stability and safety

- Marine Technology Society Journal – Maritime engineering developments